THE LORD SANDWICH ex ENDEAVOUR® COMES TO RHODE ISLAND

© RIMAP 2019

D. K. Abbass, Ph.D.

Further details are found in a number of articles, pamphlets, books, and reports published by the same author. See the RIMAP Publications list found elsewhere on this website.

The Endeavour replica. © ANMM.

The vessel that carried James Cook on his first circumnavigation was built in Whitby, a village on the eastern Yorkshire coast of England that was an important shipbuilding center for the North Sea and Baltic trade. The Whitby ships were called colliers because they were well suited to carry heavy cargoes, especially coal from northern England to London. In the 18th century Whitby was called the “seamen’s nursery” because so many sailors were trained there.

Whitby on the east Yorkshire coast of England. Base map by Wikipedia, Graphic © RIMAP 2016.

James Cook was the son of a Yorkshire farmer, and as a teenager he apprenticed to Whitby shipowner, John Walker. Walker's house is now a museum.

John Walker's house in Whitby. Photo by Bill Burns, © RIMAP 2017.

The Whitby ships were beamy and flat-bottomed. They were not designed for speed, but were merchant ships to carry heavy or clumsy loads. Local Whitby Shipwright Thomas Fishburn built a typical collier for Thomas Milner, launching her in June 1764. Her name was Earl of Pembroke.

A typical collier in Whitby Harbor, identified as the Endeavour. Painting by Thomas Luny, 1790.

In 1768 the Royal Navy agreed to support a scientific expedition to Tahiti by providing a ship and its crew. Two Royal Navy and three commercial vessels were considered for the voyage. The Royal Navy chose the Whitby collier Earl of Pembroke for that service.

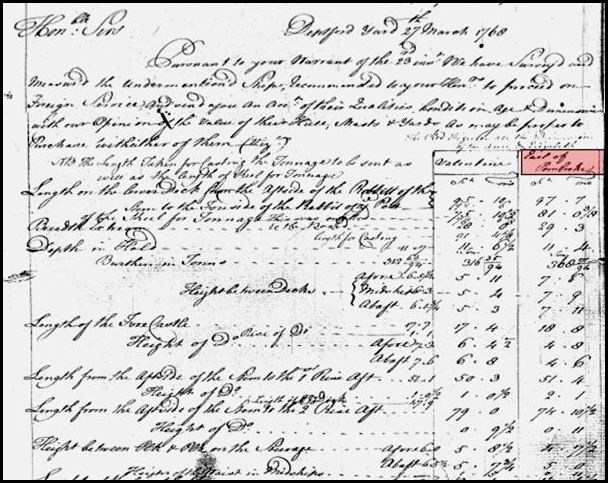

Part of the original Earl of Pembroke survey. ADM 106-3315 p. 197A.

Details about the ship and her construction are found in many documents in the National Archives in Lodnon, including the March 27, 1768, marine survey of the Earl of Pembroke that describes many of the ship's construction details. The Royal Navy shipyard also made drawings to show the ship's size and shape, and these materials were used to design and build the modern Endeavour replica.

James Cook in 1775. By Nathaniel Dance Holland, Greenwich Maritime Museum.

When the Earl of Pembroke was selected for the voyage, her name was changed to HMB Endeavour. She was square rigged but was called a "Bark" because there was another HMS Endeavour in the Royal Navy. Today sailing ships are identified by their rig types, but in the 18th century the shape of the hull, and sometimes in the Royal Navy the rank of the commanding officer, determined what a ship was called.

Because of his navigational and cartographic skills, and because of his former training and experience in colliers like theEarl of Pembroke, Lt. James Cook of the Royal Navy was appointed to command the Endeavour on the scientific voyage to observe the Transit of Venus at Tahiti.

Chart of Cook’s first circumnavigation in the Endeavour Bark, 1768-1771. Map by Wikipedia.

The observation of the Transit was not successful, but Cook's secret orders were also to explore the South Pacific and find the large land mass presumed to be there. NASA recorded the transit of Venus in 2012 which you can watch here.

Joseph Banks collected biological and ethnological materials along the voyage. Descriptions of the cultures met along the way expanded European knowledge of the world.

Cook's "observatory" for the 1769 Transit of Venus at Tahiti.

Cook did not find the presumed Great Southern Continent, but he did visit many local islands. Then he circumnavigated New Zealand, where he met violent resistance from fierce Maori warriors.

Joseph Banks and ethnological artifacts collected on the voyage. Portrait by Benjamin West, 1771.

A Maori war canoe 1770. By Herman Sporing, Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand.

From New Zealand the Endeavour sailed to southeastern Australia, where Cook and his crew met very different people.

The Australian kangaroo. Painting by George Stubb in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

As the Endeavour sailed along the east coast of Australia, she was badly damaged when she went onto the Great Barrier Reef. Cook saved the vessel by throwing overboard 40-50 tons of iron and stone ballast, spoiled stores, and all but four of the ship's guns. In 1969 six of these cannons were found and conserved, and they are now displayed in three Australian cities, and in Philadelphia, Wellington, and London.

The conserved cannon retrieved from the Great Barrier reef on display in New Zealand. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Once the Endeavour was off the reef, she sailed to a nearby river, where her flat bottom was an advantage for repairs. That river is now called the "Endeavour River."

The Endeavour repaired in the Endeavour River. Engraved by William Byme after Sydney Parkinson, 1773. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

The Endeavour then continued her voyage, and at the north tip of Australia Cook claimed that continent for Britain. The year 2020 will be the 250th anniversary of that claim. More repairs at the Dutch shipyard in Batavia (today's Jakarta, Indonesia) allowed the Endeavour to return to England in 1771 and the next year Cook sailed in the Resolution for his second voyage around the world.

The Endeavour then continued to serve as a Royal Navy store ship, carrying supplies three times to the Falkland Islands between 1771 and 1774.

The United Kingdom and the Falkland Islands. Graphic from CNN

The Endeavour was then sold to J. Mather and returned to private service, making a trip to Archangel in Russia.

The United Kingdom and Archangel. GoogleEarth.

By 1775 conditions in North America were leading up to the Revolution, and Mather offered the Endeavour as a transport to carry troops to serve in that conflict. The Endeavour was at first refused for that service because of her poor condition, but after some repair and a name change to Lord Sandwich, she was accepted and carried Hessian mercenaries to the British colonies.

The British Landing at Kip's Bay, New York, 1776. Robert Clevely, Royal Museums, Greenwich. This image is often mis-identified as the occupation of Rhode Island in 1776.

After the British abandoned Boston in March of 1776, they turned to Rhode Island, especially to control Newport's Harbor. In December British and Hessian troops occupied the two largest islands of Narragansett Bay. The Lord Sandwich transport was in the fleet of vessels that carried these occupying troops. By this time, Cook was sailing on his third voyage around the world, again in the Resolution.

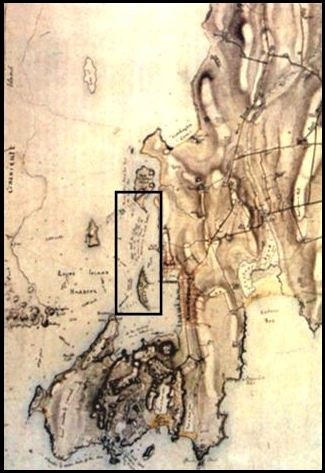

The 1777 map of Rhode Island by Blaskowitz. Many versions extant.

While in Rhode Island, the British transports were used to carry troops to and from New York, and especially to collect fuel wood at Long Island. The transports Lord Sandwich and Rachel and Mary, and possibly other ships, were used as prisons for captured American patriots. Local citizens suspected of mischief in 1777 were also kept on the Lord Sandwich until the American threat that year was over.

Aquidneck is the large island in the middle of Narragansett Bay, with Newport at its south end. Conanicut Island is to the west.

The British originally planned to attack Providence and retake Boston, but the Patriots controlled the mainland around Narragansett Bay, and stopped those British plans. Instead, there were many engagements between the British and Patriots, especially along the shores of the Bay.

Part of the list of prisoners kept on board the Lord Sandwich transport in 1777. Original in the Newport Historical Society, Graphic © RIMAP 2002.

The Ozanne drawing of the French fleet entering Narragansett Bay, August 8, 1778. Original in the Library of Congress. Graphic © RIMAP 2015.

In the Spring of 1778 the French joined the American cause and sent a fleet and army to help the Patriots, and on July 29 the French arrived at Rhode Island. The British ordered the Royal Navy vessels stationed in Narragansett Bay and the Sakonnet River to self-destruct rather than be captured, and seven eventually did so.

This contemporary drawing of the French fleet’s entry into Narragansett Bay on August 8 confirms the transport locations by the masts standing proud from the water. Original in the Library of Congress. Graphic © RIMAP 2015.

The British sent as many as 30 transports and privately owned vessels to Newport’s Inner Harbor for safety and posted three of their Royal Navy vessels at the north and south end of Goat Island to protect the Inner Harbor entrances. The British also scuttled 12 transports in the Outer Harbor to act as a blockade and to protect the city from the French as they entered the Bay. A 13th transport was set on fire and lost north of Goat Island.

The 1779 Fage chart shows where the transports were scuttled in Newport's Outer Harbor. Original chart at the Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Graphic © RIMAP 2017.

The ensuing Siege of Newport and Battle of Rhode Island failed to change the balance of power, and the British abandoned the area in 1779. When the French arrived under Rochambeau in 1780, they began taking up equipment from the British transports scuttled in the Outer Harbor. This continued until the Providence businessmen, who had bought the rights to the property left behind by British, complained to General Rochambeau, the French commander. It is unknown how much gear the French sailors removed and how much was taken up by local Rhode Islanders, but 40 years later parts of the harbor were still congested with their remains.

This Rochambeau chart shows where the French anchored their vessels in a Vauban arrangement to control the entrance to the Bay. The rectangle also shows where some of the scuttled British transports were located. Chart from the US National Archives. Graphic © RIMAP 2017.

RIMAP has spent many years teasing out the 19th- and 20th-century history of Newport Harbor, in an effort to determine what further processes would contribute to an understanding of what happened to the transport fleet. Some of those conclusions are found in the other essays on this website.